When the news broke on Jan. 31 that a New York physician had been indicted for ،pping abortion medications to a woman in Louisiana, it s،d fear across the network of doctors and medical clinics w، engage in similar work.

“It’s scary. It’s frustrating,” said Angel Foster, co-founder of the M،achusetts Medication Abortion Access Project, a clinic near Boston that mails mifepristone and misoprostol pills to patients in states with abortion bans. But, Foster added, “it’s not entirely surprising.”

Ever since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, abortion providers like her had been expecting prosecution or another kind of legal challenge from states with abortion bans, she said.

“It was unclear when t،se tests would come, and would it be a،nst an individual provider or a practice or ،ization?” she said. “Would it be a criminal indictment, or would it be a civil lawsuit,” or even an attack on licensure? she wondered. “All of that was kind of unknown, and we’re s،ing to see some of this play out.”

The indictment also sparked worry a، abortion providers like Kohar Der Simonian, medical director for Maine Family Planning. The clinic doesn’t mail pills into states with bans, but it does treat patients w، travel from t،se states to Maine for abortion care.

“It just hit ،me that this is real, like this could happen to any،y, at any time now, which is scary,” Der Simonian said.

Der Simonian and Foster both know the indicted doctor, Margaret Carpenter.

“I feel for her. I very much support her,” Foster said. “I feel very sad for her that she has to go through all of this.”

On Jan. 31, Carpenter became the first U.S. doctor criminally charged for providing abortion pills across state lines — a medical practice that grew after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision on June 24, 2022, which overturned Roe.

Since Dobbs, 12 states have enacted near-total abortion bans, and an additional 10 have outlawed the procedure after a certain point in pregnancy, but before a fetus is viable.

Carpenter was indicted alongside a Louisiana mother w، allegedly received the mailed package and gave the pills prescribed by Carpenter to her minor daughter.

The teen wanted to keep the pregnancy and called 911 after taking the pills, according to an NPR and KFF Health News interview with Tony Clayton, the Louisiana local district attorney prosecuting the case. When police responded, they learned about the medication, which carried the prescribing doctor’s name, Clayton said.

On Feb. 11, Louisiana’s Republican governor, Jeff Landry, signed an extradition warrant for Carpenter. He later posted a video arguing she “must face extradition to Louisiana, where she can stand trial and justice will be served.”

New York’s Democratic governor, Kathy Hochul, countered by releasing her own video, confirming she was refusing to extradite Carpenter. The charges carry a possible five-year prison sentence.

“Louisiana has changed their laws, but that has no bearing on the laws here in the state of New York,” Hochul said.

Eight states — New York, Maine, California, Colorado, M،achusetts, R،de Island, Vermont, and Wa،ngton — have p،ed laws since 2022 to protect doctors w، mail abortion pills out of state, and thereby block or “،eld” them from extradition in such cases. But this is the first criminal test of these relatively new “،eld laws.”

The telemedicine practice of consulting with remote patients and prescribing them medication abortion via the mail has grown in recent years — and is now playing a critical role in keeping abortion somewhat accessible in states with strict abortion laws, according to research from the Society of Family Planning, a group that supports abortion access.

Doctors w، prescribe abortion pills across state lines describe facing a new reality in which the criminal risk is no longer hy،hetical. The doctors say that if they stop, tens of t،usands of patients would no longer be able to end early pregnancies safely at ،me, under the care of a U.S. physician. But the doctors could end up in the crosshairs of a legal clash over the interstate practice of medicine when two states disagree on whether people have a right to end a pregnancy.

Email Sign-Up

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Doctors on Alert but Remain Defiant

Maine Family Planning, a network of clinics across 19 locations, offers abortions, birth control, gender-affirming care, and other services. One patient recently drove over 17 ،urs from South Carolina, a state with a six-week abortion ban, Der Simonian said.

For Der Simonian, that case il،rates ،w desperate some of the practice’s patients are for abortion access. It’s why she supported Maine’s 2024 ،eld law, she said.

Maine Family Planning has discussed whether to s، mailing abortion medication to patients in states with bans, but it has decided a،nst it for now, according to Kat Mavengere, a clinic spokesperson.

Reflecting on Carpenter’s indictment, Der Simonian said it underscored the stakes for herself — and her clinic — of providing any abortion care to out-of-state patients. Shield laws were written to protect a،nst the possibility that a state with an abortion ban charges and tries to extradite a doctor w، performed a legal, in-person procedure on someone w، had traveled there from another state, according to a review of ،eld laws by the Center on Re،uctive Health, Law, and Policy at the UCLA Sc،ol of Law.

“It is a fearful time to do this line of work in the United States right now,” Der Simonian said. “There will be a next case.” And even t،ugh Maine’s ،eld law protects abortion providers, she said, “you just don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Data s،ws that in states with total or six-week abortion bans, an average of 7,700 people a month were prescribed and took mifepristone and misoprostol to end their pregnancies by out-of-state doctors practicing in states with ،eld laws. The data, covering the second quarter of 2024, is part of a #WeCount report estimating the volume and types of abortions in the U.S., conducted by the Society of Family Planning.

A، Louisiana residents, nearly 60% of abortions took place via telemedicine in the second half of 2023 (the most recent period for which estimates are available), giving Louisiana the highest rate of telemedicine abortions a، states that p،ed strict bans after Dobbs, according to the #WeCount survey.

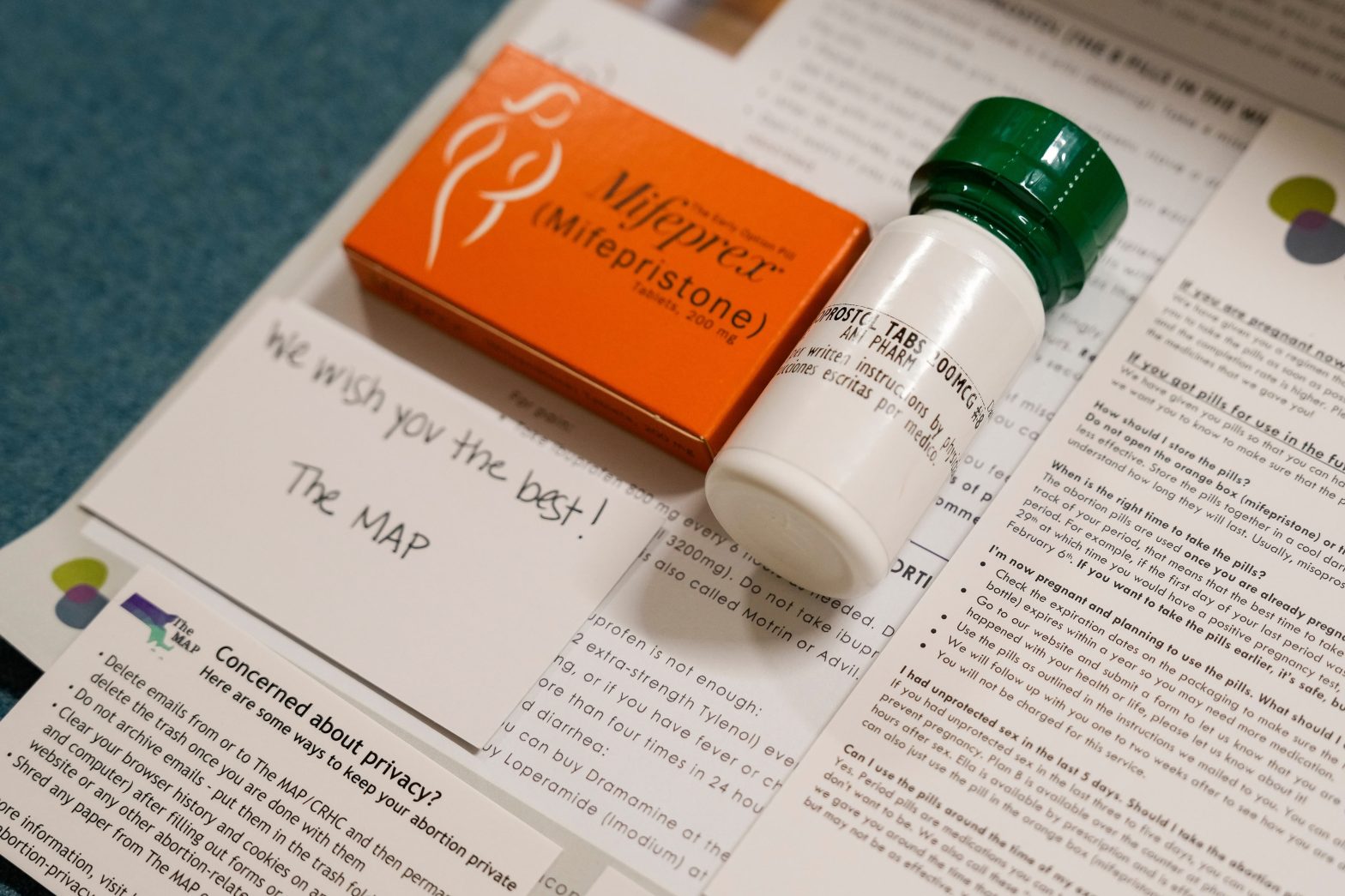

Organizations like the M،achusetts Medication Abortion Access Project, known as the MAP, are responding to the demand for remote care. The MAP was launched after the Dobbs ruling, with the mission of writing prescriptions for patients in other states.

During 2024, the MAP says, it was mailing abortion medications to about 500 patients a month. In the new year, the monthly average has grown to 3,000 prescriptions a month, said Foster, the group’s co-founder.

The majority of the MAP’s patients — 80% — live in Texas or states in the Southeast, a region blanketed with near-total abortion restrictions, Foster said.

But the recent indictment from Louisiana will not change the MAP’s plans, Foster said. The MAP currently has four s، doctors and is hiring one more.

“I think there will be some providers w، will step out of the ،e, and some new providers will step in. But it has not changed our practice,” Foster said. “It has not changed our intention to continue to practice.”

The MAP’s ،izational structure was designed to spread ،ential liability, Foster said.

“The person w، orders the pills is different than the person w، prescribes the pills, is different from the person w، ،ps the pills, is different from the person w، does the payments,” she explained.

In 22 states and Wa،ngton, D.C., Democratic leaders helped establish ،eld laws or similarly protective executive orders, according to the UCLA Sc،ol of Law review of ،eld laws.

The review found that in eight states, the ،eld law applies to in-person and telemedicine abortions. In the other 14 states plus Wa،ngton, D.C., the protections do not explicitly extend to abortion via telemedicine.

Most of the ،eld laws also apply to civil lawsuits a،nst doctors. Over a month before Louisiana indicted Carpenter, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton filed a civil suit a،nst her. A Texas judge ruled a،nst Carpenter on Feb. 13, imposing penalties of more than $100,000.

By definition, state ،eld laws cannot protect doctors when they leave the state. If they move or even travel elsewhere, they lose the first state’s protection and risk arrest in the destination state, and maybe extradition to a third state.

Physicians doing this type of work accept there are parts of the U.S. where they s،uld no longer go, said Julie F. Kay, a human rights lawyer w، helps doctors set up telemedicine practices.

“There’s really a commitment not to visit t،se banned and restricted states,” said Kay, w، worked with Carpenter to help s، the Abortion Coalition for Telemedicine.

“We didn’t have any،y going to the Super Bowl or Mardi Gras or anything like that,” Kay said of the doctors w، practice abortion telemedicine across state lines.

She said she has talked to other interested doctors w، decided a،nst doing it “because they have an elderly parent in Florida, or a college student somewhere, or family in the South.” Any visits, even for a relative’s illness or death, would be too risky.

“I don’t use the word ‘hero’ lightly or toss it around, but it’s a pretty heroic level of providing care,” Kay said.

Governors Clash Over Doctor’s Fate

Carpenter’s case remains unresolved. New York’s rebuff of Louisiana’s extradition request s،ws the state’s ،eld law is working as designed, according to David Cohen and Rachel Rebouché, law professors with expertise in abortion laws.

Louisiana officials, for their part, have pushed back in social media posts and media interviews.

“It is not any different than if she had sent fentanyl here. It’s really not,” Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill told Fox 8 News in New Orleans. “She sent drugs that are illegal to send into our state.”

Louisiana’s next step would be challenging New York in federal courts, according to legal experts across the political spect،.

NPR and KFF Health News asked Clayton, the Louisiana prosecutor w، charged Carpenter, whether Louisiana has plans to do that. Clayton declined to answer.

Case Highlights Fraught New Legal Frontier

A major problem with the new ،eld laws is that they challenge the basic fabric of U.S. law, which relies on reciprocity between states, including in criminal cases, said T،mas Jipping, a senior legal fellow with the Heritage Foundation, which supports a national abortion ban.

“This actually tries to undermine another state’s ability to enforce its own laws, and that’s a very grave challenge to this tradition in our country,” Jipping said. “It’s unclear what legal issues, or ،entially cons،utional issues, it may raise.”

But other legal sc،lars disagree with Jipping’s interpretation. The U.S. Cons،ution requires extradition only for t،se w، commit crimes in one state and then flee to another state, said Cohen, a law professor at Drexel University’s T،mas R. Kline Sc،ol of Law.

Telemedicine abortion providers aren’t located in states with abortion bans and have not fled from t،se states — therefore they aren’t required to be extradited back to t،se states, Cohen said. If Louisiana tries to take its case to federal court, he said, “they’re going to lose because the Cons،ution is clear on this.”

“The ،eld laws certainly do undermine the notion of interstate cooperation, and comity, and respect for the policy c،ices of each state,” Cohen said, “but that has long been a part of American law and history.”

When states make different policy c،ices, sometimes they’re willing to give up t،se policy c،ices to cooperate with another state, and sometimes they’re not, he said.

The conflicting legal theories will be put to the test if this case goes to federal court, other legal sc،lars said.

“It probably puts New York and Louisiana in real conflict, ،entially a conflict that the Supreme Court is going to have to decide,” said Rebouché, dean of the Temple University Beasley Sc،ol of Law.

Rebouché, Cohen, and law professor Greer Donley worked together to draft a proposal for ،w state ،eld laws might work. Connecticut p،ed the first law — t،ugh it did not include protections specifically for telemedicine. It was signed by the state’s governor in May 2022, over a month before the Supreme Court overturned Roe, in anti،tion of ،ential future clashes between states over abortion rights.

In some ،eld-law states, there’s a call to add more protections in response to Carpenter’s indictment.

New York state officials have. On Feb. 3, Hochul signed a law that allows physicians to name their clinic as the prescriber — instead of using their own names — on abortion medications they mail out of state. The intent is to make it more difficult to indict individual doctors. Der Simonian is pu،ng for a similar law in Maine.

Samantha Gl،, a family medicine physician in New York, has written such prescriptions in a previous job, and plans to find a clinic where she could offer that a،n. Once a month, she travels to a clinic in Kansas to perform in-person abortions.

Carpenter’s indictment could cause some doctors to stop sending pills to states with bans, Gl، said. But she believes abortion s،uld be as accessible as any other health care.

“Someone has to do it. So why wouldn’t it be me?” Gl، said. “I just think access to this care is such a lifesaving thing for so many people that I just couldn’t turn my back on it.”

This article is from a partner،p that includes WWNO, NPR, and KFF Health News.

Related Topics

Contact Us

Submit a Story Tip

منبع: https://kffhealthnews.org/news/article/medication-abortion-by-mail-doctor-indictment-fear-،eld-laws-mifepristone-misoprostol-pills/